Written by: Samina Ahmed

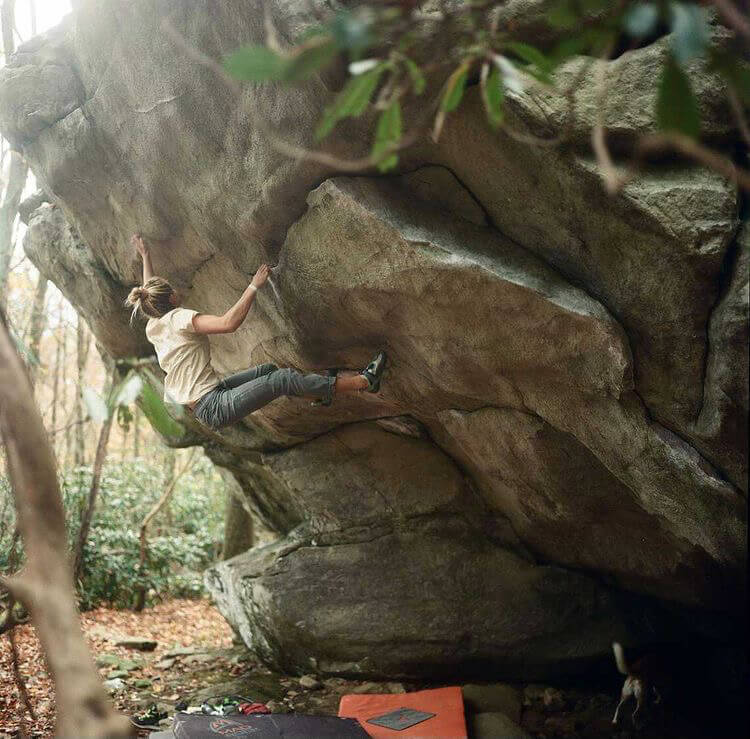

Rock climbing has always seemed to me a language unto itself. Climbers dance on the routes they attempt with unparalleled dedication and motivation so inherent it rivals poetry. Some of the most literate people I know can read without words, and their movement on the rock tells stories worth sharing. These stories are written first by nature, into the stone we are lucky enough to climb on, and then retold by athletes who understand the language. I am always enchanted by climbers who are good at reading routes, and especially those who like to leave notes in the margin.

I met 21 year old Katy Brayman amongst a group of friends in Utah during the winter of 2021. We were warming up on some easy boulders in Joe’s Valley. The valley is on the outskirts of an old mining town, and strewn with world-class sandstone boulders. It was a crisp, late winter morning and the group of us were wearing puffy jackets and sipping coffee. As we took turns scaling easy problems, I noticed Katy’s climbing. It wasn’t so much what she climbed as how she climbed that caught my attention. She seemed at home on the rock, at home in her body. The effort it takes to climb well, the culmination of hours spent training and all the sacrifices it requires, was apparent. What I could also see was the integration of movement and lifestyle. Katy does not boast or make a scene. She climbs as casually as somebody making breakfast.

Katy grew up in Rhode Island climbing trees and building forts. Her hometown sounds idyllic when she describes it, and would make anyone feel nostalgic for their own childhood haunts. Katy’s first passion is surfing, and currently she has also taken up jiu jitsu. She works as a surf instructor and spends her summers on the water. She’s quick to point out that surfing and jiu jitsu are hobbies, while rock climbing is a lifestyle. When I ask Katy how long she has been climbing, she hesitates. “I’ve been climbing for four years. When I was seven I climbed on a climbing team for a year. A friend in town was also on the team, so I was able to get a ride with her. When she moved away… I had to quit climbing. I was devastated, for my whole life, basically.” Katy lets out a little laugh. I smile as she recounts this to me because I can see the devotion in her eyes. As soon as Katy was old enough to drive herself to the gym, she picked up right where she left off. She trained and climbed whenever she had the opportunity. It surprises me to learn that Katy was once so passionate about gym climbing, since her life today is centered around creating time and space to be outdoors.

Katy explains that, at first, she felt hesitant about climbing outside. “The thought of walking up to a boulder with a large group of people standing around terrified me. Approaching a bunch of people like that seemed scary. Actually, the idea of going to the gym used to be scary, too.” When I ask her if she prefers climbing alone, she pauses and thinks about it. “I can’t say I prefer climbing alone, but a majority of the time it’s what I do. It’s a different headspace I’m in, I dive so much deeper into what’s going on with the boulder. I don’t talk to anybody, no distractions. I can just dial it in. Climbing outside by myself is a totally different experience, one that I am creating all the time.” I start to get the impression that the story of Katy’s climbing is also a story of growing up. As with any impassioned climber, Katy’s growth as a person is facilitated by the need to break barriers on the rock. Whether this means learning how to approach a large group of people, or trying something new to unlock a problem, rock climbing provides limitless opportunities for self-reflection and growth.

When I met Katy during the winter of 2021, she was in the midst of her first solo road trip, accompanied by her dog, Timber. She climbed in Joe’s Valley, then made her way to St. George, and then to Flagstaff, Arizona. During her journey, Katy’s confidence grew. The climbing community embraced her and helped her to feel safe focusing all of her energy on bouldering. She shaved her head, stopped worrying about traditional fixations, and put all of her energy into rock climbing. In Flagstaff, Katy found a problem called “The Girl” which caught her attention. Over the course of five sessions and two trips spread out over two months, she sent. The first time Katy worked the boulder she was unsure about whether she would be able to pull it off. “The thing about rock climbing is thinking, this is impossible – maybe I can do it in two years. Then after working it, you realize you are actually capable of anything if you try hard. It’s possibly my favorite thing about climbing.”

For her final session on “The Girl,” Katy was with a group of ladies she met in Flagstaff, and their encouragement helped her believe she was capable of doing the route. “It was really special to be surrounded by strong girls, you know, strong females, who actually wanted me to do the boulder. I watch the video, and I can hear them cheering for me… it makes me tear up. This trip was amazing for opening my eyes to how many strong female rock climbers there are in the community. It was cool to connect with them.” Katy has many anecdotes about building community wherever she finds herself. She is as happy working hard problems alone, as she is to be surrounded by friends, or in one case, a 12 year old boy and his grandparents.

During the spring of her road trip, Katy was visiting Redondo Beach and decided to climb at Stony Point because of its historical importance for climbers. She met a 12 year old boy who was out climbing while his grandparents supervised. “The kid’s grandparents had lawn chairs, and a picnic basket. They were just there to hang out for the day. They saw I was alone and said, hey, join us.” Katy spent her day climbing alongside and coaching her new friend, while his grandfather used an old camcorder to take videos. A week later she received an email from them, thanking her for a good time at the boulders. The grandfather wrote, “We never knew the climbing community was like this, so inclusive. You really changed our impression of rock climbers.” Katy flashes a big smile as she recounts this story, “I know if something like that had happened when I was 12… it would have been so cool. I was psyched I could have that impact on them.”

Katy’s trajectory as a climber began as a young girl and continues into adulthood. If climbing is a lifestyle, mentoring young climbers comes with the territory. So do growing pains. Katy tells me the story of a boulder named Mochuelo she climbed in Roy, New Mexico. What strikes me about this boulder problem is the fact that Katy attempted it for the first time in 2020, during a time in her life when she felt lost, and missed her dog. I can feel the sense of yearning and unease that underscores Katy’s first attempts on Mochuelo.

“I fell in love with Roy. The whole time I was there I kept thinking, I would really love to be here with Timber right now. I just wish I had my dog. Going back a year later with Timber I thought, this is it. This is where I need to be.” Same boulder, different girl. Growing up is like that – marked by new relationships with old routes. “Mochuelo means owl in Spanish, and this boulder looks like a big owl. When I get close on a boulder it gets stuck in my head. I thought about that boulder for a whole year. When I came back to Roy… I didn’t get on Mochuelo until the last day, maybe because I was nervous to discover that I had not gotten stronger.”

Nevertheless, Katy did get back on it. “When I first tried Mochuelo, there was one move I could never do. But coming back, the smallest change in my right hand – switching it from a side pull to an undercling pinch, was all I needed. I stuck the move twice. I had finally done all the moves, but I was too tired to do the boulder. I left my pads there and came back the next morning. Over the course of a full session, I ended up doing the boulder. It totally took me by surprise. It was really cool to be on top of that boulder and look down and see Timber. I was happy with where I was… that boulder had sentimental value.”

Mochuelo marked a time when Katy was proactive about making needed changes for the better. Perhaps climbing, in and of itself, doesn’t really matter. But the meaning we assign to it, the love we bring to it, and the way we are raised by the rock and rise to its demands – that does matter. Katy is an example of someone whose story is inextricably connected to the rock she reads so well.

To read more of Samina’s work head over to her site: https://www.saminaahmed.com/