by Kerim Tshimanga

Welcome to Spotting for Bouldering!

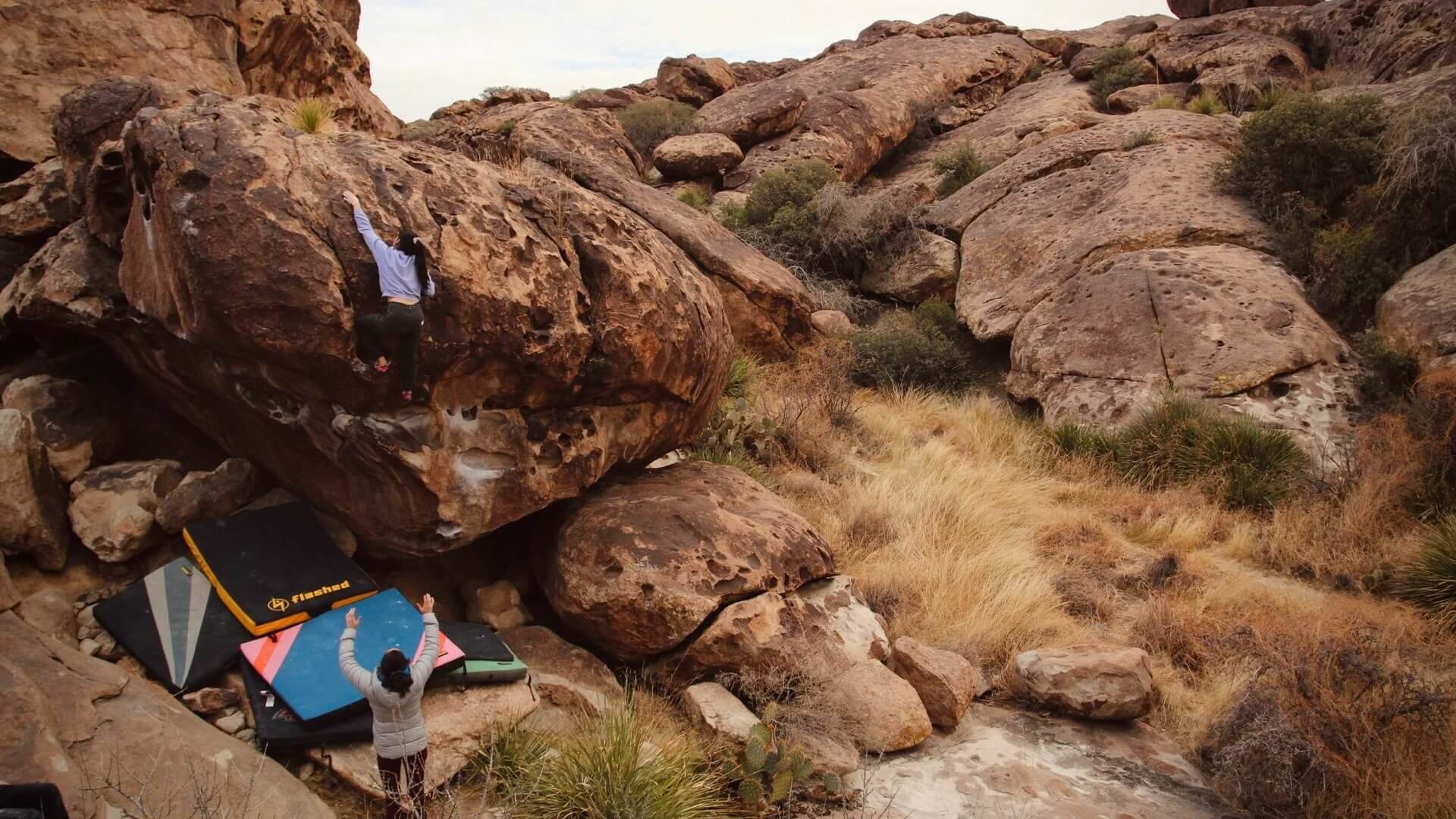

Bouldering is fun, but not without danger and sometimes climbers need an active helping hand in mitigating the dangers of a given situation. You, as the spotter, are this active helping hand. You exist because either some of the present dangers cannot be sufficiently protected with pads alone or create redundancy in safety that allows the climber to focus on climbing rather than their potential dismount concerns. The spotter plays a very important role in bouldering, and the consequences of bad spotting can be dire so we ought to set a high standard for it.

Etiquette

Before continuing, however, we should take a moment to touch on spotting etiquette. Always ask first if a climber wants a spot. Spotting isn’t always necessary. Some climbers don’t like the feeling of being grabbed while falling. Ask first, spot only with consent. Yes, I know, that person is super attractive and you’re dying to show how supportive you can be… Please don’t grope them.

Responsibility as a spotter

When you spot a climber, they often then climb with the expectation that some danger is now lessened or eliminated by your presence; and with this faith in you they likely are going to climb in a way that they wouldn’t have otherwise. Perhaps there are insufficient pads, a bad landing, they’re high up, or they’ve sunk the most secure ankle-snapping heel-toe cam. It is your responsibility to both set and live up to the climber’s expectations.

What danger is the spotter in, Spotters for spotter, and What is actually feasible

Take care to consider what danger you might be in as the spotter. Once the climber starts going most of your attention will be on your climber; however, you may also need to navigate uneven ground or drop offs. Plan how you will move with the climber ahead of time, and this gets a lot easier. In some more precarious situations, you might want to enlist a backup spotter to keep you from falling so you can dedicate more attention to your climber. Backup spotting could be as simple as someone helping you balance to wearing a harness and anchoring yourself to a crack as you lean out over an edge.

What is actually feasible and communication

Ultimately, you can often run into limits to how effectively/safely you can spot your climber. It’s important to recognize what is feasible and safe for you as a spotter. Just as important as catching falls is making sure your climber understands what you can do. If your climber is double your weight, taking falls from 20ft up, you most likely can’t give them that coveted elevator catch. Similarly, if the climb moves over a fatal drop off you simply can’t follow the climber the whole way. You should be upfront with your climber about any limitations, even if you’re simply not comfortable with the situation. It’s important that you climber has shared clear expectations with you so they can make a fully informed decision about the amount of leftover risk they are willing to take. Sometimes not all danger can be eliminated.

Multiple Spotters

Quite often when climbing in a large groups multiple people may spot all together. This can be super helpful in situations with uneven ground that is difficult to navigate or just a lot of ground to cover. Multiple spotters can be a liability though. There is only so much space on a climber’s hips for hands and multiple spotters close together can cause hesitation around who actually is going to catch the fall in the end. Ideally it is best to have each spotter responsible for a different danger or falling point along the climb so it is clear who is actually catching the climber at any point.

Dabbing

The concept of dabbing exists as a way to say that climbers should climb problems using only their own prowess. This comes up all the time in spotting particularly on problems where the climber has to hold a swing. If you inadvertently stop their swing by being in the way, that can be frustrating for the climber. This naturally creates tension between keeping the climber safe vs. not invalidating a potential ascent. In some situations, it’s fine to just not spot because failure is low consequence.

In other situations like when the swing is over a pit/cliff you might want to err on the side of caution. This is a good thing to talk to your climber about ahead of time so your priorities are aligned. One thing to note, some people take the concept of dabbing to an unhelpful extreme where they believe their climbing is invalid if they so much as kick a passing butterfly. This is obnoxious for all involved and if you have the misfortune of climbing with one of them, tread lightly and emotionally prepare yourself for unwarranted tantrums.

Proper Spotting Form

Proper spotting is situational. As a spotter, you must adapt your approach to specifically the dangers you are protecting the climber from. Simply hold your hand straight out in front of you is not sufficient. For instance, let us say your climber is on a roof with a very secure heel-toe cam. If their hands slip they will pendulum under their ankle and break it in the process. To prevent that from happening you need to be able to fully arrest them before they fallen far enough to damage their ankle and continue supporting their weight until they can dislodge their foot.

If you’re just standing there with your hands out, you will fail in your duties leaving them dangling from a freshly broken ankle. Most adult climbers weigh at least 100lbs. Have you tried holding a 100lbs kettlebell out in front of you with straight arms? Quite difficult. Similar to lifting a 100lbs+ kettlebell you’ll want to assume a position under the climber ready to grab them firmly at their center of mass and squat them from a position of power. This strategy of course isn’t appropriate for spotting an all-points-off dyno.

Landing Zone & Pads

All climbers should check that they are satisfied with the state of their landing zone before they begin climbing but since an unkept landing zone with poor pad placement can thwart even the best of spots, it is important for a spotter to take particular interest in its upkeep. Uneven pad edges, gaps, shifting pads, etc. must all be guarded against vigilantly.

Written by Bidimpata-Kerim Ntumba Aramyan-Tshimanga