by Carlos Tkacz

This happens pretty often:

I am working on a problem with someone, and we discover that the problem has some big, dynamic move in it. The person says something along the lines of, “Man, it sucks being short.”

I usually respond with something like, “Yeah, I’m tall, so I like dynos.” This statement is delivered often with a commiserating tone and understanding nod.

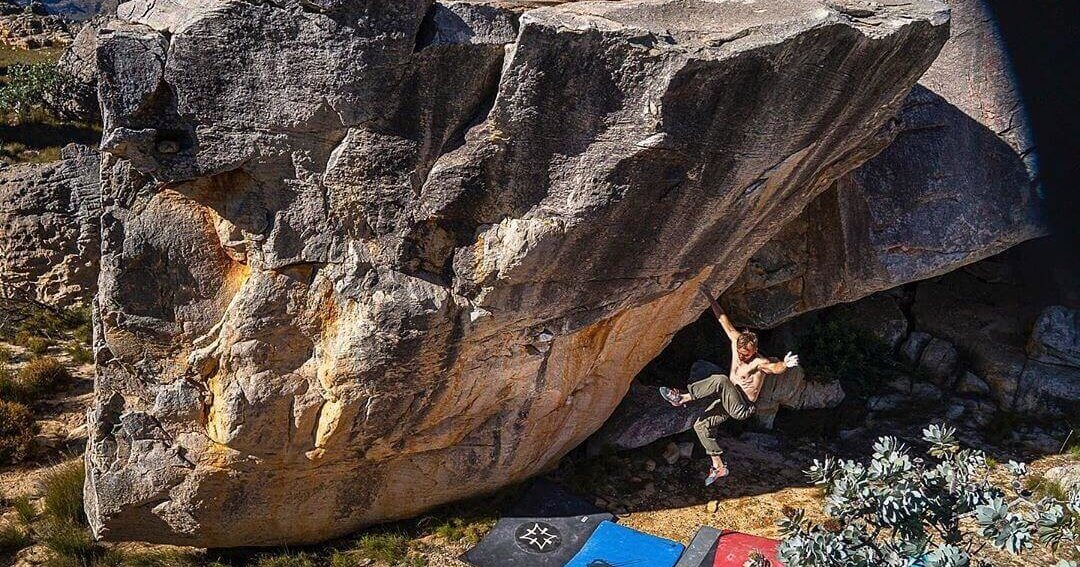

And this is true, mostly. I do like dynos. I think they’re about as fun as fun gets. Little else is as exciting to me as the split moment of airtime. The swing following the latch. The satisfaction of your body returning towards the rock with your hand still on the hold. It’s just cool, straight fun.

But this has nothing to do with me being tall (at least, I don’t think it does).

You might call me a liar at this point for responding to the person as I did, but consider this: as a tall climber, I am not allowed to be happy about being tall. That would be tantamount to rubbing in other climbers’ faces. On the same note, I am also not allowed to complain about bunchy roofs where my knees touch my chin, and my elbows graze my ankles.

Basically, I have to accept that people are going to give me shit for being tall. And hey, that’s ok by me, really. But that’s not really what I want to talk about here, back to dynos.

Soccer and Dynos

I think I can trace a pre-climbing history with dynamic movement in my life that leads directly into my love of dynos.

When I was a kid, I played keeper in soccer all the way into high school. Now, there’s a lot to be said about playing keeper, and I don’t think keepers get quite enough credit for the chaos they endure in their position, but let’s stick to the keeper’s dyno corollary: the dive.

The Dive

As a keeper, you must learn to dive. Let me try and describe the experience:

You are standing in your box, watching them play out in the field in front of you. Suddenly, the direction of movement shifts, and everyone is sprinting in your direction. You backpedal, glancing back to make sure you’re centered between the posts as the players in front of you spread out in your direction.

You yell at your defense, pointing out movements they miss and making sure the angles are covered. The offense makes a few passes; you move left or right accordingly as you watch the ball, making sure you are in a position to cover as much of the goal as possible. Then it happens.

You see an offensive player take a glance in your direction and plant their lead foot. You instantly go into a kind of hopping crouch, staying on your toes as you micro-adjust the angle between the kicker and you. The kicker’s leg swings faster than you can see, and, in an instant, the ball leaves his foot, the hours of practice kick in, and instinct throws you in a direction.

Your legs explode from the quads down to the ankles; you swing your arms hard over your head. You’re in the air, watching the ball arc in your direction. You stretch a hand as far as you can and get as much of it on the ball as possible. The impact redirects your flight back just as you reach the high point of your dive, and your legs swing up and forward while your hands come down to cushion your impact back to earth. You land hard, roll, and jump back up in a squat if the ball is still in play.

It’s pretty intense, but I realize that, probably, no one wants to read me wax poetic about the experiences of jumping around like a monkey. What I do know is that some people struggle with dynamic movements in climbing.

With that in mind, I thought I would offer some tips for dynos.

Practice!

You would think this goes without saying, but it bears repeating. You will never get better at dynamic moves if you don’t try them. My advice for this is to dedicate a portion of your climbing session to dynamics. Seek out the dyno problems in your gym or at your crag. If you can’t find any, make some up! Try all kinds too: all-points off, left-hand and right-hand leading, cross dynos (these are fun!), dynos where your lower hand stays on, dynos from different positions.

If dynos are a struggle for you, this will feel useless at first, but I promise that, slowly, you will learn and get better. Be sure to pay close attention to what is happening and reflect upon what works and what doesn’t; this is an important part of any learning process, and climbing is no different.

Fluidity of Movement

Something I often see in aspiring dyno-ers is a kind of mental block in the movement. A dyno is complex; a lot is happening. Often, climbers think a little too much about the movement and try executing it like they make other moves: one stage at a time. This results in a kind of disjointed, choppy dyno: they pull in first, then push with their legs, and finally, they reach and try to grab.

In reality, a smooth dyno-er will conduct all these steps nearly at once, the separate steps overlapping into a fluid movement in which your whole body works together AND simultaneously to get you some air. As you practice, your mind and body will learn how to multitask like this, freeing your awareness to focus on catching the next hold.

The Moment of Contact

Regardless of whether you are doing an all-points off dyno or just throwing with one hand, the moment of contact with your target hold is where it all comes together. If you can’t grab and hold, it doesn’t matter how far you can throw yourself. Often, if the hold you are going to is a HUGE jug, then there is not much to do other than grab and hold on. However, sometimes the hold you throw for is not as juggy as you’d like, or sometimes the swing is so intense that even a jug can be tough to hang on to.

The problem here is that many people focus only on grabbing the hold when, really, dyno-ing is full-body karate. Try to tense your entire body, especially your core, when your hand(s) touch the target hold. This will help you minimize any swings and will put you into an engaged state right away. Along the same lines, it is often easier to hold difficult grips when you have some engagement in your arm; try getting enough height so that you hit the hold with your arm already bent and, therefore, already engaged and pulling.

Foot Position

There are many considerations when it comes to the positioning of your feet, though, often enough, the climb itself determines this. The important thing to remember is that, generally, your legs are what drives much of the power for dynos. With this in mind, choose your feet to optimize the power. Too high, and you won’t be able to get your weight over your feet to drive your body upwards. Too low, and you won’t have the room to generate momentum through the extension of your legs. Also, keep in mind that it is easier to jump from bigger feet. Sometimes, it is worth using a larger foot that is in a slightly worse position, as you will be able to drive harder from it. All this, though, should be considered with the next two points in mind.

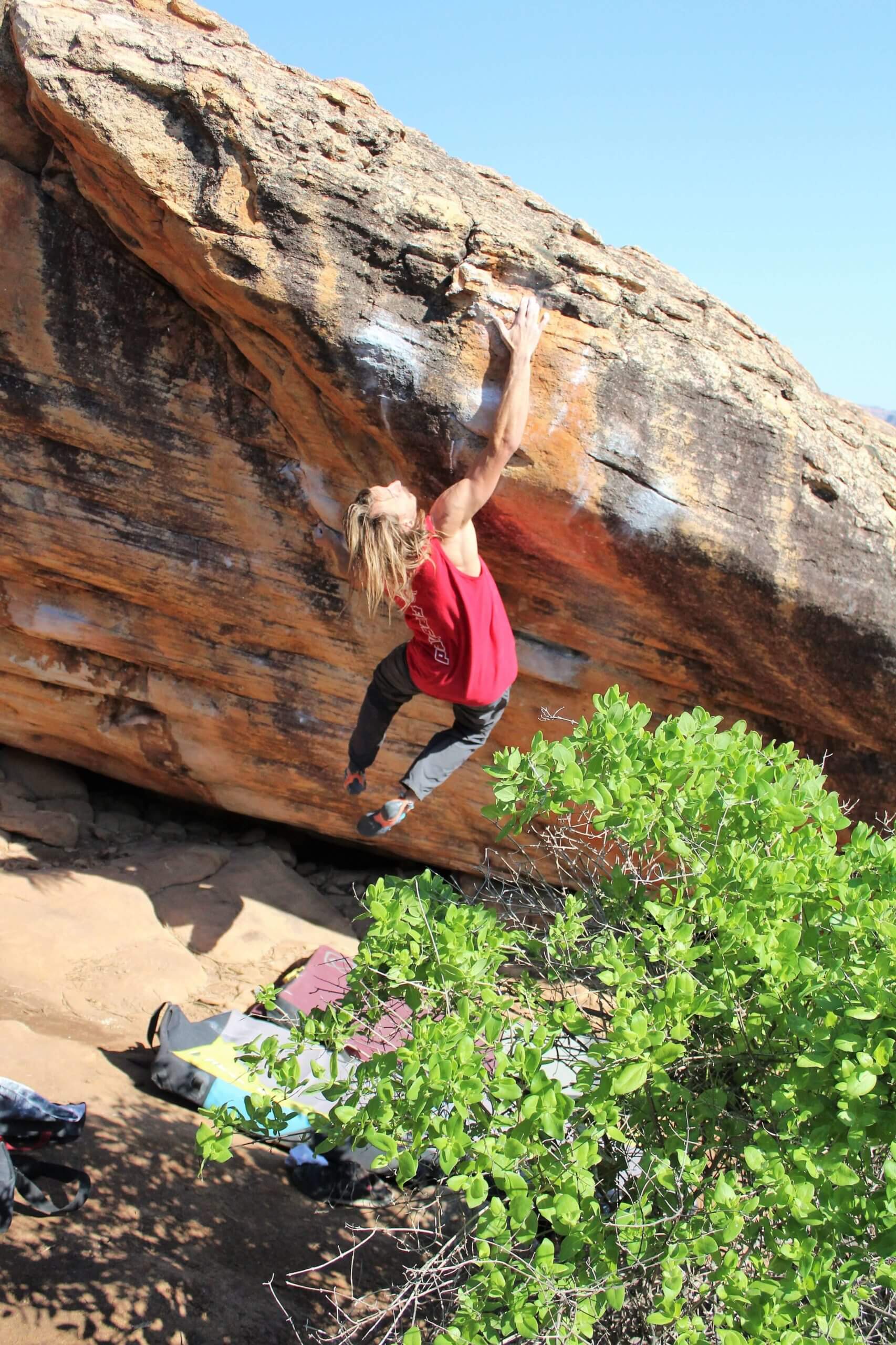

The Role of the Arms

While it is true that the legs drive most of your momentum, this depends a bit on the dyno. Generally, the steeper the dyno, the more your arms will have to help in generating power. That said, the primary function of your arms in a dyno is to direct your body. Sometimes, this means pulling your weight over your feet so you can jump up and not out. Sometimes, this means using your arms to swing your weight to one side, so you jump at an angle. Regardless, think of your arms as the steering wheel for your legs, the engines. Keep in mind the point about Fluidity of Movement; the arms and legs work TOGETHER, not separately.

The Hips

The hips are also important; I often see people struggling to stay close enough to the wall when dyno-ing. They jump, ass out, and fly at an angle that sends them back from the wall rather than flushes with it. You can help with this issue by focusing some mental energy on driving with your hips. As you are pulling through and jumping up, drive your hips up and towards the wall. This will bring your center of gravity closer to the rock and direct your trajectory closer.

Commitment

This is something I have had to work on, personally. Oftentimes, fear keeps people from dyno-ing as hard as they can, and this is perfectly understandable. There is something kind of scary about dynos – the sense of control you often seek in climbing is thrown out, and, instead, you have to accept a certain amount of chaos. The best way to deal with this fear and increase your commitment is to work out the safety issues before getting on the rock. Get some spotters you trust and plan with them about the best place to spot, the best pad placement, and the most likely outcomes of snagging the dyno and missing it.

Basically, have a conversation about this before you get on the rock so that, when you do, you can focus on what you are doing, not on what could happen. Then, if you miss your jump, have another conversation with your spotters about what happened, good and bad, and adjust your plan accordingly. Finally, keep your eyes on the hold you are going for! Often, myself included, people will jump and immediately look down, basically giving up on their attempt before they even start!

Landing (AKA, the Miss)

Chances are, if you are trying a hard dyno or are practicing, you’re going to fall plenty. Good falling technique, in general, is important in bouldering; I skated when I was young, and I learned how to fall while throwing myself off 10 stairs onto concrete and asphalt. First of all, stay loose: stiffening up is a good way to hurt an ankle or knee when you land. Your body will do what it needs to do if you let it. After all, it has X number of years practicing keeping you upright throughout your life. Rather than turning into a board and letting the kinetic energy of your impact jolt its way through your joints and spine, let your body absorb the fall by staying loose so you can fall in stages in concert with the directional energy of your momentum. Basically, don’t fight it!

Secondly, as you are falling, scope your landing. When you are on your way back down, it is ok, now, to take a glance at where you are going to hit. This visual information will help your body instinctually act with a better understanding of your positioning in space. Lastly, keep those arms in! Often, people shoot a stiff-arm out to try and catch themselves; this is a good way to break a bone. Stiff-arms are like brittle branches – they snap! Rather, keep your hands in, and elbows close so you can absorb the impact on the bigger, fleshier parts of your body: your back and shoulders. This’ll hurt, no doubt, but these parts of your body can handle impact better than an outstretched hand.